The last decade in Canada has marked a turn in the general public opinion of cannabis use. This change is also happening internationally – medical cannabis has recently been legalized in Mexico, Germany, and Australia – with conversations everywhere starting to evolve. Depending on who you ask, the pace of legalization seems quick for some, and lagging for others. Looking at the history of Canadian cannabis, popular opinion has waxed and waned, but as science catches up with myth, we are ushering a new era of drug policy.

It would seem like an obvious starting point, but fact-based evidence has been slow to impact the conversation around cannabis. Thankfully, we are starting to see published results from recent research. Think Tanks are joining the conversation, both long-running institutions like Brookings, and new faces like NICHE, and Volteface – a UK think tank that looks at alternatives to current public policies around drugs. Volteface’s first policy paper, ‘Tide Effect’, starts with a line borrowed from Victor Hugo: “There is nothing as powerful as an idea whose time has come”.1

Then

If there’s an idea that’s been waiting on the sidelines for its time to come, it’s the legalization of cannabis. While it was widely used in medicine in the early 20th century, a variety of factors led the drug to be classified as a narcotic in Canada by 1923. Between the late ’20s and late ’40s, the Depression and WW2 occupied the politics of the country.

When international drug policy discussions came to a head in the ’50s and early ’60s, Canada signed on to international conventions. This resulted in a doubling of the maximum sentence of drug-related offences, and then a few years later the maximum number of years (14) became the minimum sentence. This caused quite a stir in Canadian society, resulting in a ‘Commission of Inquiry’ (The Le Dain Commission: 1969 – 1972). The role of the commission was to investigate the role government and courts should play in regulating the use and distributions of drugs used for nonmedical purposes.

This period of Canadian history, around the 100 year anniversary of the country’s formation, is an interesting time where our shared values start to shift. The anti-war movement came North with the American draft dodgers. Immigration laws opened our doors to migrants outside of Britain, the US and Europe for the first time. The social forces in the ’60s and ’70s pushed the government to structure more inclusive policies rather than the former model of assimilation. Of course, not all traditions of incoming communities were readily accepted.

The Le Dain inquiry was symbolic of a greater controversy over lifestyles and political participation, and it operated in an atmosphere of controversy. Canada came very close to decriminalizing cannabis after the inquiry. A bill to take cannabis out of the Narcotic Control Act and create more lenient sentencing was passed in the Senate, but was not approved in the House of Commons.

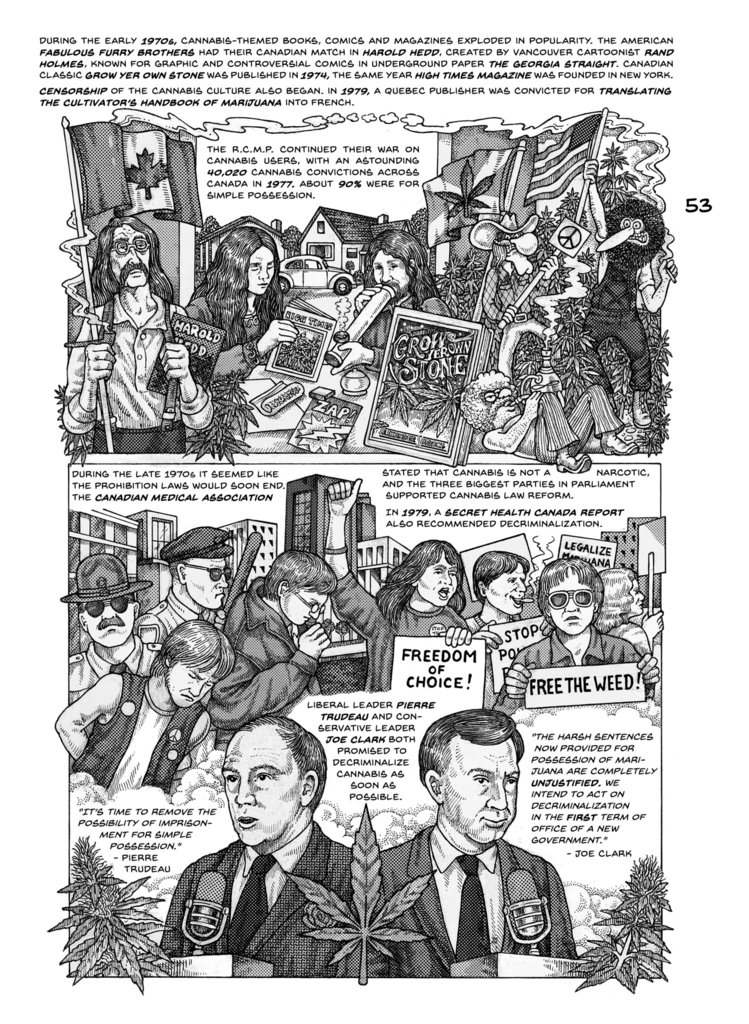

An excerpt from Dana Larsen’s ‘Cannabis in Canada – The Illustrated History’ 2

Now

The first laws around Canadian cannabis were introduced in 2001 with the birth of the ‘Medical Marijuana Access Regulations (MMAR), and have seen a few different court challenges and iterations to bring us up to the current ‘Access to Cannabis for Medical Purposes Regulations’ (ACMPR) which came into effect in 2016. Fast forward to 2017, where springtime saw Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announce the upcoming legalization of cannabis. On Thursday, June 8th, the bill had its second reading, and was referred to the Standing Committee on Health.

The first pass of legislation is being developed by the federal government and covers the production of cannabis. The provinces and territories will licence and supervise the distribution and sale, according to any federal conditions. According to the backgrounder from Health Canada: ‘Roles and Responsibilities’, provinces and municipalities could also adjust rules based on the values of their jurisdictions.

“These rules may include:

- Licensing the distribution and retail sale in their respective jurisdictions, and carrying out associated compliance and enforcement activities;

- Setting additional regulatory requirements to address issues of local concern. For example, provinces and territories could set a higher minimum age or more restrictive limits on possession or personal cultivation, including lowering the number of plants or restricting where it may be cultivated;

- Establishing provincial and territorial zoning rules for cannabis-based businesses;

- Restricting where cannabis may be consumed; and

- Amending provincial and territorial traffic safety laws to address driving while impaired by cannabis (e.g., providing for 24-hour licence suspensions for adults or zero tolerance for young drivers).”3

These items of concern were derived from a series of consultations with the public, industry professionals, and policy experts. The feedback was gathered, analyzed, and summarized by the commissioned ‘Taskforce on Legalization and Regulation of Cannabis in Canada’. The taskforce included professionals from the areas of medicine, law, policing, and policy.

Members of Parliament will return to the House of Commons on Monday, September 18th, leaving them 220 work days to live up to their promise to pass legislation by July 1st, 2018.

Beyond

The next iteration of Canadian cannabis policy development is being led by NICHE. The not-for-profit group “intends to operationalize the Taskforce report by ensuring all stakeholders […] are equipped in their fields to manage this new regime”.4 NICHE is an independent organization that bridges academic research, law makers, the Canadian cannabis industry, and public health and safety partners. They want to create a collaborative, transparent and fact based approach to legalization in Canada.

Canadian cannabis is on the forefront of a global shift towards decriminalization and legalization. These are exciting times, even though there is still so much to be decided. It’s not very often that we get to witness the birth of a new industry, let alone be the thought leaders behind this world issue.

1 – Starling, Boris. “1. The Independent On Sunday.” London, UK, Volteface, 2016, pp. 9, volteface.me/publications/tide-effect/the-independent-on-sunday/.

2 – Larsen, Dana. “The Early 1970s.” Cannabis In Canada: An Illustrated History, Hairy Pothead Press, 2015, p. 53.

3 – Canada, Health. “Backgrounder: Roles and Responsibilities.” Canada.ca, Government of Canada, 13 Apr. 2017, www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2017/04/backgrounder_rolesandresponsibilities.html.

4 – Rasode, Barinder. “Mandate.” National Institute for Cannabis Health and Education / NICHE Canada, NICHE, 29 Mar. 2017, www.nichecanada.com/mandate.